A Review by David Finkelstein

for filmthreat.com (4 stars out 5) July 15, 2010

A theater director, Alex (played by the director of the film, Antero Alli), brings a troupe of nine actors to a remote forest to engage in paratheatrical work. For those of you unfamiliar with this term, it refers to a range of practices, inspired by Polish theater pioneer Jerzy Grotowski, in which the techniques of theater are used, not to create works of art to be performed for an audience, but solely for the personal and spiritual development of the participants. This explains why, in the film, a full production with costumes, make-up and props is being staged without an audience in a remote wilderness. Since, in real life, Alli is engaged in paratheatrical research, it becomes obvious that the film’s fictional story is constructed out of documentary elements.

The work they are doing is an attempt to realize French poet and playwright Antonin Artaud’s vision of an explosive, transformative form of theater which he called the “Theater of Cruelty.” They are using texts by Artaud as well as from “The Tempest” and “Romeo and Juliet” by Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s language, so passionate and precise, may be the perfect vehicle for trying to channel this unruly energy.

Alex is tormented by repeated nightmares in which he is taunted by the ghost of Artaud. He avoids sleeping for days in order to prevent these dreams from coming back. The film alternates between many levels of reality: depictions of the theater troupe’s forest work, Alex’s “video diaries” in which he tries to make sense of his deteriorating mental state, dream sequences featuring Clody Cates’ astonishing performance as the (female) spirit of Artaud, and extensive sequences in which Alex desperately seeks help through hypnosis, administered by a therapist, played in a sensitive performance by Garret Dailey. A sense of disorientation is increased throughout the film when, for example, Alex frequently falls into a trance in the doctor’s office and seems to wake up in his tent in the forest, or vice versa.

In the fascinating dialogues with the doctor, both Alex and the doctor challenge each other to expand their own world-views. Alex understands the cosmic Void as being a source of potential energy which creates everything, and the doctor finds this difficult to grapple with. The doctor understands some basic mechanisms about emotion which Alex has been ignoring at his peril. Subtly, the dialogue critiques the limits of both psychotherapy and art as avenues of self-exploration. (Alex is visibly surprised when he learns that the doctor has studied dream work directly from the aboriginal people of Australia, and isn’t as limited in his perspective as Alex had previously assumed.)

In a wonderfully bizarre dream cabaret scene, Artaud’s ghost performs a vaudeville act in which she directly humiliates the doctor, who is a symbol for the discipline of psychology, with its need to reduce the mysteries of spiritual adventures to a set of easily understood personal problems. Antonin Artaud, after all, embraced his own mental illness as a liberating force, and waged a life-long losing battle against his psychiatrists.

The montages of the actors in the forest, reciting fragments of Shakespeare and Artaud, make up a great deal of the film as well, and the powerfully grounded and elemental performances of the entire cast make these scenes particularly gripping. Often, they look, paradoxically, so real they could be from a dream. In fact, it is never made clear which of the altered states these scenes come from: paratheatrical work, hypnosis, dreams, or induced trance states.

James Wagner as "Hermes the Dream Ego"

James L. Wagner, crouching in a tree, gives an astonishing performance in a monologue from Artaud’s “New Revelations of Being.” In his headlong, ecstatic embrace of the Void, he embodies the will to madness with which the spirit of Artaud is tempting Alex. Wagner is vibrant with crazed revelation.

As the film progresses with its increasingly disorienting mix of mental states, it induces in the viewer some of the same alternate levels of consciousness which form its subject matter. Artaud is trying to get Alex to liberate himself from the obsession with particular artistic “forms,” and to instead embrace a way of being which surrenders directly to energy. The film, which was created through improvisations instead of a script, embodies this principle of art-making in its process. A repeated image of silver apples, like those in the poem by Yeats, symbolizes this temptation to awaken to a new life.

The haunting music is by long-time collaborator Sylvi Alli, along with Sean Blosl, David Rosenbloom, and several others. “The Invisible Forest” is full of treasures. It is able to depict those elusive mental states which prove so hard to remember or describe when we awaken from dreams. This film incites and dares the viewer to let go of concepts and accept the risky adventure of following the free, unimpeded energies of the body and mind.

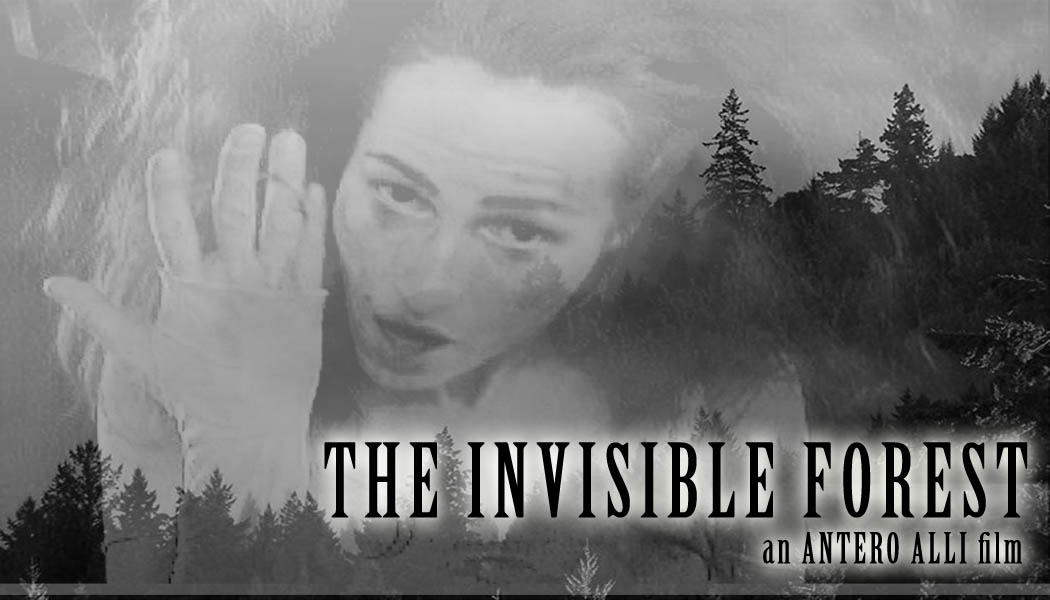

THE INVISIBLE FOREST

the movie site